When news of the Armenian Genocide reached Australia through Anzac eyewitness accounts and media reports, the pain and suffering of the Armenian people caused great consternation throughout the country.

An Australian fund for the survivors of the Armenian Genocide first emerged in Victoria in late 1915 called the Armenian Relief Fund. In March 1917, the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Sir David Hennessy, together with other prominent Victorians, agreed to set apart a Sunday in April for special collections on behalf of the Armenians. The appeal was a great success and Melbourne newspapers reported that over £2,000 had been collected as a result. This mayoral initiative, supported by Victoria’s church leaders, became the first major grassroots drive in Australia for the stricken Armenians. By 1918, Armenian relief committees were also formed in Sydney and Adelaide.

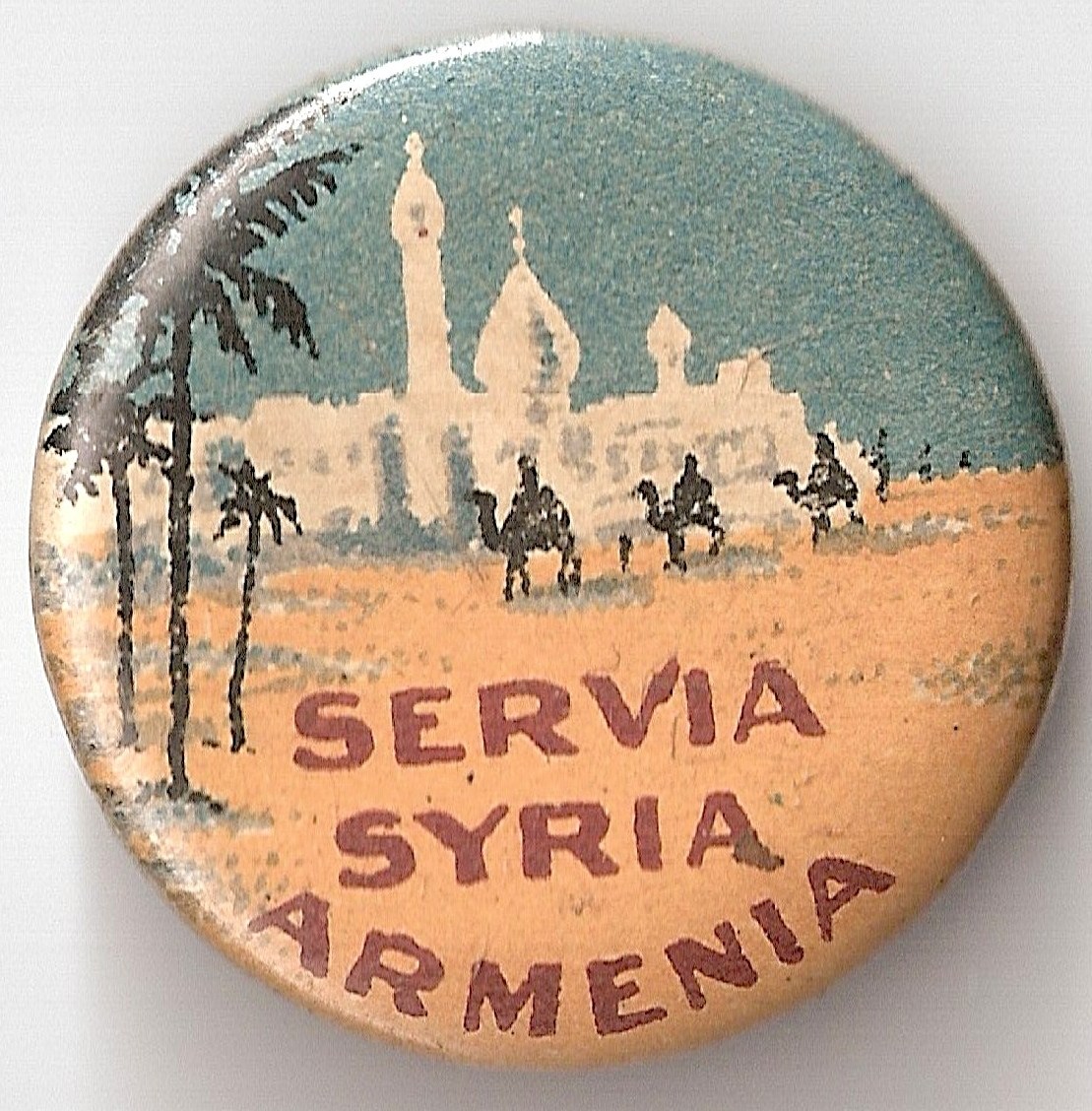

Badge produced by the Commonwealth Button Fund of Australia for Armenian relief in 1917.Source: Australian War Memorial Archives, Canberra. See http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/REL39129/

Ottoman Turkey’s defeat during the First World War (WWI) and the ensuing Mudros Armistice, signed on 30 October 1918, brought a glimmer of hope to the exiled Christians. However, the disunity of the European Powers towards the defeated Ottoman Empire and the establishment of a Turkish nationalist movement in 1919, thwarted any attempts to protect the safety and security of the surviving Armenians. While the end of WW1 brought peace to the belligerent nations, the Armenians continued to suffer renewed persecution. Australians such as Red Cross nurse, Sister Isobel Hutton, were at the forefront in providing relief to the approximately 70,000 "wearied, frightened, hungry" and desperate Armenian refugees in Aleppo, Syria in 1919. The desperate plight of the Armenians intensified the mobilisation of humanitarian activism back home in Australia during the interwar period.

In 1920, a movie called the Auction of Souls was shown throughout Australia which was based on the story of Aurora Mardiganian, an Armenian girl who had survived the Armenian genocide. It was premiered in Sydney on 11 January 1920 at the Sydney Town Hall to a sell-out crowd. The NSW Minister of Education, Mr James, gave an introductory remark about the importance of the movie in providing awareness to Australians of the desperate plight of the Armenians. According to film historian, Leshu Torchin, it was the first movie ever made explicitly as a work of advocacy for humanitarian relief.

The first major shipment of relief supplies collected in Australia for the survivors of the Armenian Genocide. Anglican Archbishop of Melbourne, Harrington C. Lees, together with other clergy are seen blessing the flour at Port Melbourne, 5 September 1922.

By 1922, relief committees were operating in every state in Australia and a national executive committee was formed headquartered in Adelaide, South Australia. The Rev. James Edwin Cresswell, a Congregationalist minister from Adelaide, was unanimously appointed as national secretary of the Australasian Armenian Relief Fund. The Australian relief committees soon established an orphanage in Antelias, Lebanon, called the Australasian Orphanage. It housed about 1,700 Armenian orphans who had survived the Armenian Genocide. The director of the orphanage was Captain John Knudsen, an Anzac veteran of WWI. Major appeals for aid were launched throughout Australia. Within a short time, over $100,000 (about $1.5 million in today's terms) worth of relief supplies were collected and shipped to the refugee centres in the Near East. The Prime Minister of Australia, Billy Hughes, promised that free freight would be provided by the Commonwealth Steamers (Australian government shipping vessels) for the goods collected by the relief committees.

Australian Reverend James E. Cresswell, Hilda J. King and Miss Gordon with orphaned Armenian Genocide survivors at the Australasian Orphanage, Antelias, Lebanon, 1923. Source: 'The Armenian Monthly', Armenian Relief Fund of South Australia, May, 1923.

Many Australians were at the forefront in providing relief to the survivors of the Armenian, Greek and Assyrian Genocides who found refuge in Greece, Syria, Lebanon and Armenia. Back home in Australia, the Armenian relief movement had mobilised a broad spectrum of Australia’s religious, civic and political leaders. The Armenian relief committees continued their work until the early 1930s. As a result of the Australian response to the Armenian Genocide, a significant number of Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians were saved from death and destitution. In Australia, this landmark response was an early manifestation of the humanitarian ethos that formed part of the nation’s engagement with international movements in the interwar period. It is also considered to be Australia’s first major international humanitarian relief effort.

Student Exercise: For a large collection of newspaper articles on Australia's humanitarian response to the Armenian Genocide, go to http://www.armeniangenocide.com.au/australianarchive and follow the research instructions under the National Library of Australia section.